In Honor of Assata and Our Ancestors: The Struggle for Life

It is my heartfelt belief that all the people on this earth deserve justice: social justice, political justice, and economic justice. I believe it is the only way that we will ever achieve peace and prosperity on earth. — Assata Shakur

Source: Hood Communist

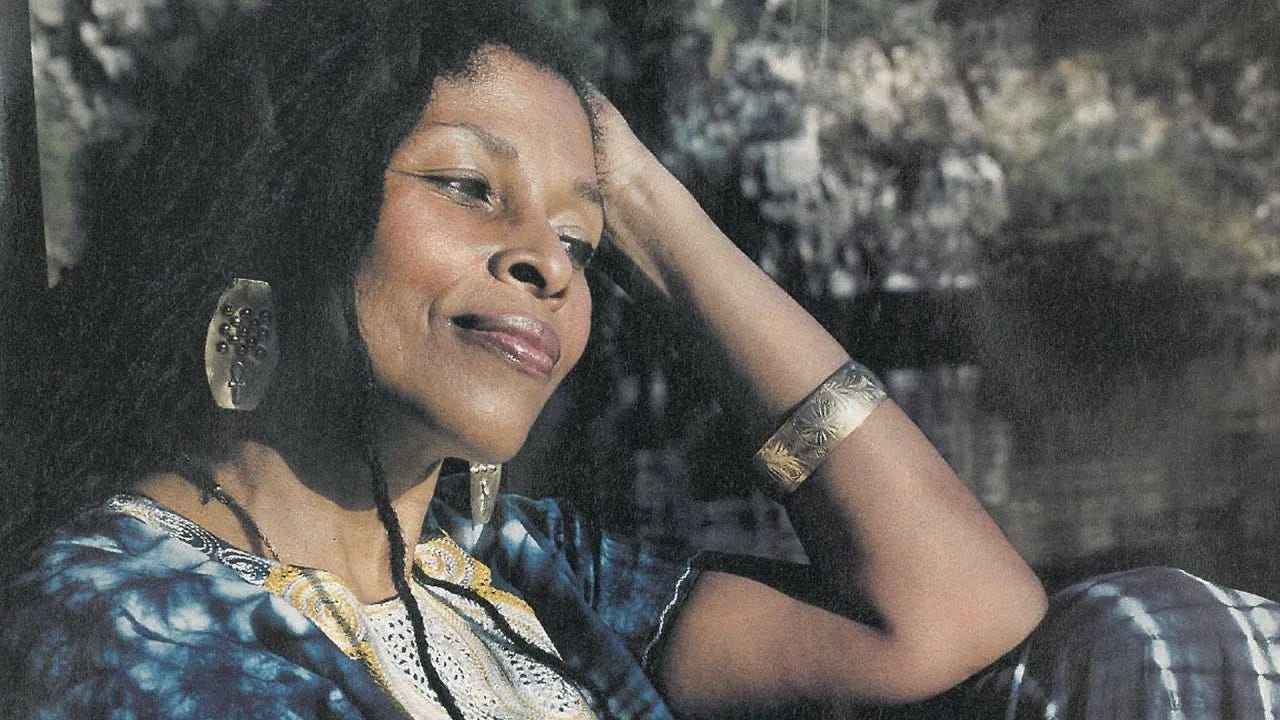

With the passing of great Black freedom fighter and revolutionary Assata Shakur (may she rest in eternal power), we have gained another ancestor. Shakur has long been venerated among those who engage in political struggle and rightly so. For many of us her political consciousness, actions, wisdom, and steadfast commitment to Black liberation provide inspiration for what it means to engage in principled struggle against oppression. There’s much to say about Assata, but what follows are a few of my reflections on the lessons and legacy she leaves us in her transition.

On the terms of war

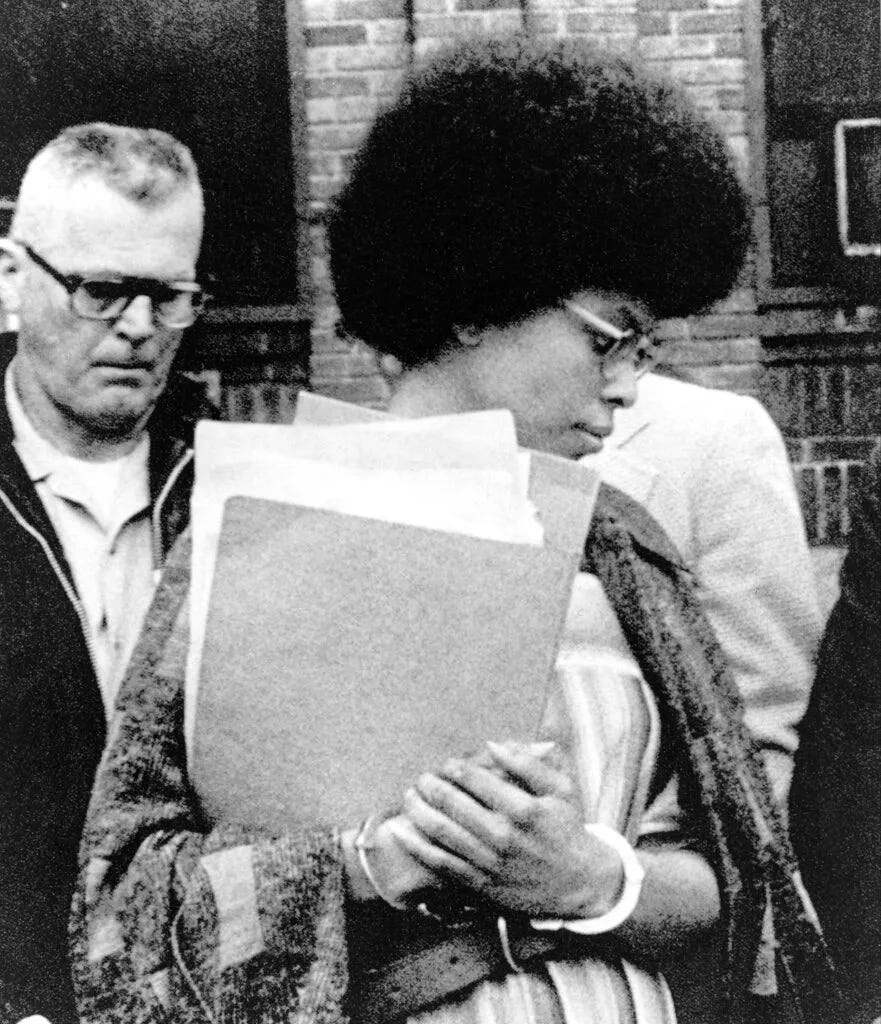

I find myself returning to one of Assata’s famous offerings, To My People (1973), which she wrote from prison after being shot by the police on the New Jersey Turnpike. Pulled over for a busted taillight, Assata was ambushed by the police. This incident resulted in the murder of Assata’s comrade, Black Liberation Army member Zayd Malik Shakur, and a life sentence in prison for Assata for killing a New Jersey police officer. This ambush was a violent act that can absolutely be understood in terms of war. In To My People Assata writes of war. Her opening paragraph states:

“I am a revolutionary. A Black revolutionary. By that i mean that i have declared war on all forces that have raped our women, castrated our men, and kept our babies empty-bellied.”

Assata saw herself as at war against the state because she understood that the state had already declared war against her. Her life experiences proved this point. To be Black in America was to be targeted by state violence. By the time she was incarcerated in 1973, she had already witnessed the FBI’s COINTELPRO program assassinate several Black Panther Party members — and that same year, after the state murdered her comrade Zayd Malik Shakur, she became a lifelong political prisoner.

It is instructive to understand our current conditions in terms of war. This also reminds me of last month’s discussion with Orisanmi Burton, author of Tip of the Spear (2023), who likewise insists that we are at war with the state. Burton explains that this “war” framework reminds us that oppressed communities cannot expect the state to abide by its own laws, because what we are up against is not a series of isolated inequalities but an ongoing state project of domination. Reading our conditions through war, as Assata, Burton, and others urge, clarifies both what we are up against and what we must fight for. This means that there is no law, policy, political figure, or campaign that can secure liberation for oppressed people. This is particularly important to understand in our current political moment, as both mainstream parties embrace fascist policies. The fight is for liberation — not for a nicer, kinder, gentler cage or oppressor. And, if war clarifies what we are up against, then Assata’s writings also help us reject the false categories through which the state defines us and our struggle.

Source: AP Photos

Reject frameworks given to us by the state

Writing as a so-called “criminal” from prison, Assata proclaims:

“It should be clear, it must be clear to anyone who can think, see, or hear, that we are the victims. The victims and not the criminals. It should also be clear to us by now who the real criminals are. Nixon and his crime partners have murdered hundreds of Third World brothers and sisters in Vietnam, Cambodia, Mozambique, Angola, and South Africa.”

She situates the death and destruction the United States inflicts upon countries around the globe as criminal violence. This analysis is valuable, particularly as the U.S. remains responsible for orchestrating violence worldwide. Political leaders want us to believe that the carnage in Haiti, Sudan, Congo, Palestine, and elsewhere are not crimes of war, but rather a necessary and acceptable price to maintain Western hegemony. Assata continues on to speak about the violence inflicted upon Black people by the state:

“They call us murderers, but we do not control or enforce a system of racism and oppression that systematically murders Black and Third World people.”

This too reminds me of last month’s conversation where Orisanmi Burton spoke with clarity about violence, describing the state’s violence as one-sided violence. That is to say that the state attempts to monopolize violence, telling us what is and is not violence and what is and is not criminal. Assata also offers us a different theory, too rejecting the state’s claims: we are the victims, not the criminals. This is not to say that we are helpless but it’s to more accurately dislocate the state as a neutral actor. It’s helpful to continuously deconstruct what we see as violence: Houselessness and the commodification of land are violent, hunger is a violent output of capitalism, pollution and environmental harm is violent.

Communities and individuals trying to survive under these conditions is not a similar type of violence. And, resistance against the state (although at times violent) is not synonymous with harm or criminality. State definitions of what is criminal and what is violence often entraps us in cycles where we begin to see each other as the enemy, taking the focus away from the state. We demonize certain types of political action, we become scared of Black youth and police one another, we fight to protect our property instead of embracing collectivism. As Assata also said, “Only a fool lets someone tell them who the enemy is.” We should instead focus our attention on ending state violence and the conditions that allow it. When interpersonal harm occurs in our communities, we deserve responses to harm that don’t deepen violence through policing or incarceration.

Our struggle for liberation is about the fight to live

My final reflection is about life. Articulating how Black life is constituted by death under our current conditions, Assata writes,

“Black life expectancy is much lower than white and they do their best to kill us before we are even born.”

I understand Assata to be, at least in part, articulating reproductive violence. Death surrounds what it means to be Black in this country so much so that the beginning of life is often marked by death. This reminds me of what reproductive justice thinkers and organizers teach us about what reproductive violence is: the inability to raise one’s children free from state harm and violence. The violence that Black parents face while bringing life into this world can be understood as reproductive violence: neglect from the medical system, the devaluing of Black doulas and midwives, separating children from their parents at birth. This reproductive violence extends to Black children’s later years through state violence. Here, I’m thinking about Samara Rice and other countless Black parents who have had to witness their babies be murdered by the state. I am also thinking about Black parents who are forced to “share” custody of their children with the state, parenting children that are locked in cages. (More on this as we continue reading Mali Collins’ Scrap Theory next month).

Our brothers and sisters OD daily from heroin and methadone. Our babies die from lead poisoning. Millions of Black people have died as a result of indecent medical care. This is murder. — Assata Shakur

Beyond reproductive violence, I’m also considering all of the ways the state makes life unlivable. We often understand things like addiction, depression, and suicide to be individual hardship, but to what extent are they structural ones? The other day I watched a TikTok where a young Black person was speaking about their battle with suicidal ideation, saying that they are unable to journal away the stress of having no money. They articulated the weight of feeling as though they’ll never escape the constant anxiety of having to make money to live a decent life but being unable to do so. That their life will feel this way for the foreseeable future was unbearable.

People often turn to drugs to escape the violence that constitutes life under our current conditions, or to suicide to escape a world in which they feel isolated and hopeless — a world they feel is often not worth living in. This, too, is a form of state violence: murder by a system that makes life impossible.

At it’s core our struggle for liberation is a struggle for the ability to live fully, to resist not only the bullets and cages of the state, but also the slow deaths it imposes on our minds and spirits. And because of this, to believe in liberation is to believe and fight for life. As Assata said:

“Revolution is love because my undying love for the people compels me to fight so that the people can finally have some peace, so the people can feel loved.”

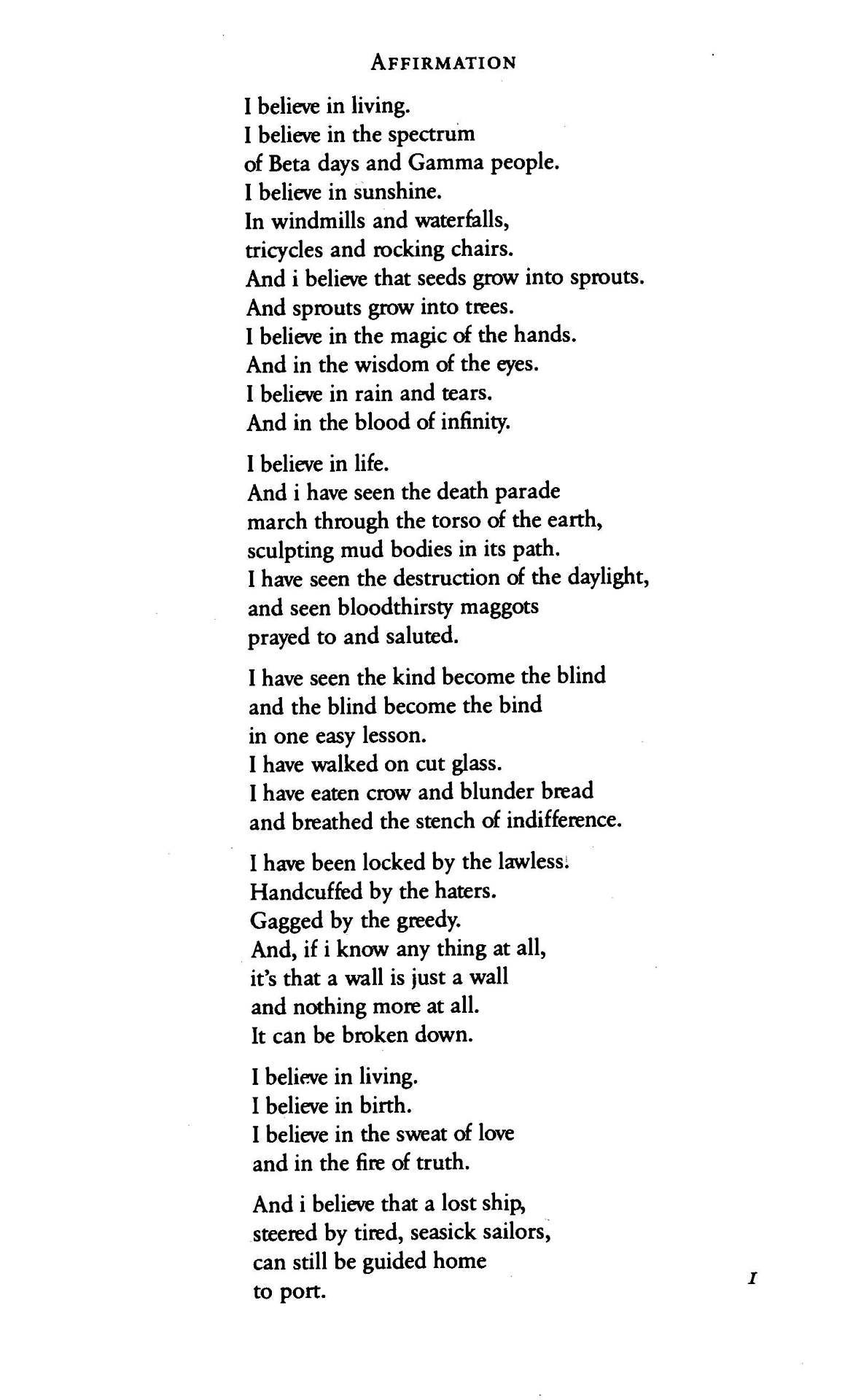

We honor Assata and our ancestors by continuing to fight for life. The struggle is long, but Black life is a struggle worthy of our commitment. Finally, I’ll leave you with this, perhaps one of my favorite writings by Assata:

Rest in Power and Love, Assata. Free them all!

A scheduling note: The past few months have been challenging for all of us, including the Toward Liberation team. To give ourselves — and you — more time to sit with each book, we are shifting to a bi-monthly reading and meeting schedule. This means our conversation on Scrap Theory with author Mali Collins will take place in October, and we’ll reconvene for our following selection in December. Stay tuned for the updated date for the Scrap Theory discussion.