Onward | Year End Reflections from Toward Liberation

Alan, connease, and Maya consider what 2025 meant for liberatory struggle

It’s hard to put into words what this year has been like. I think I share the feelings of many when I say that the world feels overwhelming and heavy and full of grief. We’ve watched a genocide continue on relentlessly, the continued destruction of life in Haiti, Sudan, and Congo, Donald Trump is once again president, ICE feels more outwardly violent than ever, and the ongoing, everyday violence of racial capitalism and the carceral state churns forward. I’m always looking for ways to understand the circumstances we find ourselves in, in a pursuit of uncovering new potentialities for how we might live better lives. Working with my dear comrades connease and Alan on upEND and Toward Liberation are ways I find what I am looking for. This work helps me see and contribute to what often feels impossible to imagine given our current realities: the big and small movements that are being made to build something better. I hope Toward Liberation is a space where others too find understanding and possibility in the midst of a far too cruel and chaotic world.

We are approaching the end of the year, and this time of year welcomes reflection. Thinking about the conversations we’ve had in community with those of you who attend our meetings, I feel hopeful and grateful. We’ve wrestled with big questions like what is violence and who gets to use it? How do we support those on the inside? What conditions make a revolution more imminent and how do we work towards them? How do we learn from Black mothers and their efforts to protect motherhood and their children? How can we engage in more liberatory faith practices? And how do we practice new worlds? We’ve been joined by inspiring abolitionist thinkers: Orisamni Burton, Andrea Ritchie, Mali Collins. They have generously lent us their time and ideas, pushing us to think deeper about how abolition becomes more possible.

So as the year closes, Alan, connease, and I wanted to leave you with a few reflections about the year we’ve had, the conversations we’ve enjoyed with all of you, and what we are thinking about as we enter 2026. — Maya

******

This year has been difficult for many of us. With the rise of authoritarian and fascist movements globally, it can feel like the left is losing ground. As you reflect on 2025, how are you making sense of the political moment we’re in?

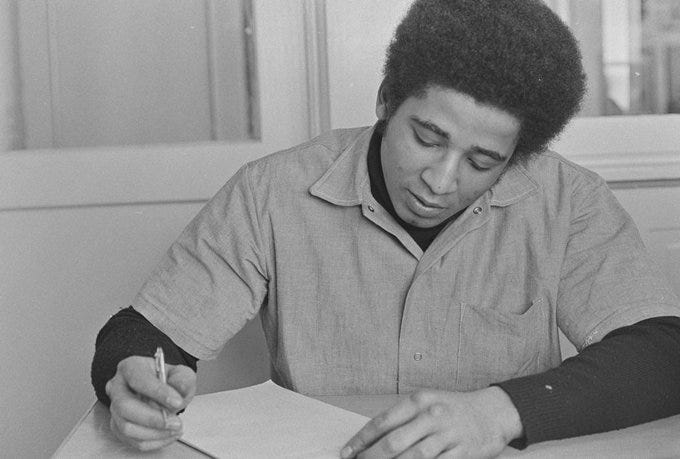

Alan: When I try to make sense of this political moment, I keep returning to the words of George Jackson, written from a prison cell in the late 1960s:

“Settle your quarrels, come together, understand the reality of our situation, understand that fascism is already here.” – George Jackson

What stays with me is not just his warning about what was coming, but his insistence that fascism was not a future threat—it was already present, already killing people who could be saved, already producing what he called “butchered half-lives.”

That framing helps ground me today. While many people now experience authoritarianism and fascism as something new or unprecedented, for Black, Indigenous, and other historically oppressed communities in the United States, this has long been a lived reality. State violence, mass incarceration, family separation, forced displacement, and premature death are not recent developments; they are foundational features of this country. Remembering this doesn’t make the present any less frightening, but it clarifies what we are actually facing and how long people have been resisting it.

It also sharpens my understanding of where fascism comes from. The danger isn’t Donald Trump or any single administration. Those are symptoms, not the source. The deeper problem is the United States itself—a political project built on genocide, slavery, racial capitalism, and imperial violence. As long as those foundations remain intact, authoritarianism is not an aberration but a recurring feature, repeatedly taking new forms.

Part of what makes this moment feel so destabilizing for many people is that, for a long time, certain forms of violence were kept at a distance—buffered by privilege, proximity, or illusion. What feels like a sudden descent into fascism is, for others, the expansion of conditions they have always lived under.

Naming that isn’t about shaming; it’s about clarity. It reminds us that the task before us is not to return to a safer past, but to confront a system that has never been safe.

connease:

I’ve struggled deeply with the realities of this moment. The brazen nature of terrors unleashed no longer bothers to throw up even a shoddy veneer of pretense. The casual cruelty wrought by White Supremacist fascists has been gut-wrenching to witness. And the assaults against the most vulnerable are relentless. Even knowing that cruelty is the point and a strategy to keep us scattered and frayed psychologically and emotionally. The gloves are off in a way they haven’t been in modern history.

It’s difficult to look upon that brazenness and recognize it as a gift. However, the violence that has always been hiding in plain sight is now on full display. Trump is but a true-to-life caricature of the racist, xenophobic sentiments that the two-party duopoly has sought to obscure with political decorum. The quiet, unspoken violence is now being shouted from the rooftops at the highest levels of U.S. government, from POTUS and his cabinet to Congress and SCOTUS. The gift in it all is the clarity needed to form a mass movement of resistance. As groups are targeted one by one, I believe and pray it will become ever evident that the 1% has the same death-making plans for all but themselves. And I hope that evidence spurs us into action.

It has been exhausting to understand the depths to which a lack of political education is hampering our collective progress.

And yet, I have been encouraged by the abundance of increasingly sharp analyses that connect the present with our shared histories across identities and continents that all point to the same root cause: White supremacy, settler colonialism, patriarchy, heteronormativity, ableism, and every other ism that obscures us from our shared destiny.

Amongst the ruins of this year, I cling to an abiding hope.

Maya: For me, the hardest part of the year has been this overwhelming feeling that what we are up against is vast in both power and strength, and that we on the left are neither organized nor aligned enough to make a meaningful dent in it. Things feel like they are moving full steam ahead, and it often seems as though there is little we can do to slow, let alone stop, the momentum. I’ve felt this especially as we witness the ongoing genocide in Palestine and the U.S.’s continued support of Israel. Many of us have made space for political education, contributed funds to efforts on the ground in Gaza, shared information, pressured politicians, attended protests, and boycotted companies, yet none of this feels like enough. The genocide continues, even as the media speaks of a “ceasefire.” That feeling of helplessness, or of simply not doing enough, has been overwhelming.

It has also become clearer than ever that there is no real political resistance to fascism within mainstream politics. Democrats have largely responded by moving rightward. And when those on the left attempt to hold politicians accountable for their spineless positions, liberals respond by accusing us of wanting “purity politics.” It’s been deeply frustrating, and that’s an understatement.

But what this political moment makes overwhelmingly clear to me is that we’ve reached a point of no return. There is no viable path back to how things used to be. Making sense of this moment means recognizing that we need strong, unapologetic left political movements, and that we can no longer afford to elect right-wing Democrats who create the very conditions for fascism to thrive. If anything, 2025 has clarified that we have to be committed to doing things differently than we have before.

Veteran Black anarchist Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin says it plainly:

“We can’t organize the way we organized back in the 60s, we can’t organize

the way we organized even 30 years ago, 20 years ago. We’ve got to break

new political ground and have new political theory and new political tactics.”

– Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin

This is something I’m thinking about recurrently. We haven’t fully adapted to the modern political landscape we’re up against, particularly in how we think about what resistance looks like. I don’t think we can afford to organize mass protests with no demands and no plans for how to mobilize people afterward. We have real work to do to modernize our political strategies if we want to win.

What’s one moment (good or bad) that felt particularly instructive for you this year?

Alan: One moment that felt especially instructive for me was the shooting of United Healthcare CEO Brian Thompson by Luigi Mangione (which occurred in the final weeks of 2024, but dominated political and social conversation well into 2025). What struck me most was not the act itself, but the response to it. There was no universal outrage or shared consensus that this violence was incomprehensible. Instead, many people—across political, racial, and class lines that rarely align—expressed a sense that the act was understandable, even justified, given the immense harm caused by the private health insurance industry.

I found this moment instructive because it exposed a widening rupture between official narratives of legitimacy and people’s lived experiences of harm.

When institutions are so clearly organized around profit at the expense of human life, faith in those institutions erodes. The public response suggested that corporations, courts, and the law are increasingly understood not as neutral arbiters of justice, but as systems that normalize slow, bureaucratic violence while criminalizing responses to it.

For me, this underscored a long-standing abolitionist insight that resistance does not always look polite, orderly, or sanctioned by the state. It often emerges when people recognize that the systems governing their lives are fundamentally unresponsive to their survival. That doesn’t make violence inevitable but it does mean we should pay attention to what people are saying when they refuse to defend institutions that have consistently failed them—and consider what that refusal reveals about resistance.

connease: One word: Chicago. Chicago’s response to ICE raids. I stayed attuned to the developments on the ground by closely following long-time organizer Kelly Hayes through her Facebook page and Organizing My Thoughts newsletter. As a quick aside, in the dearth of credible mass media, it is essential to seek voices that illuminate truth and tell stories uncorrupted by corporate interests, which is to say the interests of empire. Co-author with Mariame Kaba of Let This Radicalize You (a 2024 TL selection), Kelly’s experience as an activist, combined with a clear, pragmatically hopeful voice, continues to be a gift to the movement and is so very necessary for this moment.

But even mainstream social media told stories of Chicago’s resistance to the terror ICE unleashed on Chicago’s communities. In the hometown of Fred Hampton, people joined together to obstruct ICE with ever determined and creative means.

Chicago showed the world what is possible with organized resistance. Many put their bodies on the line to protect their neighbors, friends, and even strangers who were being hunted like prey. Chicago’s residents didn’t stop every arrest, but undoubtedly they thwarted many. The vast majority seemed unified in delivering the message that ICE was unwanted in their city, successfully branding ICE agents social outcasts barred from restaurants and city property.

Chicago’s mayor, Brandon Johnson, responded to demands from the community to increase efforts to protect Chicagoans. And in a rare show of support for community activism from the highest level of government, he often and unapologetically verbally sparred with the Trump administration, validating what boots-on-the-ground activists were doing and, from a political platform, elevating the importance of resistance. As the terror wore on, it was both shocking and refreshing to hear a sitting mayor call out the complicity of capitalism in what was happening and name-check economic resistance as a solution.

“If my ancestors, as slaves, could lead the greatest general strike

in our nation’s history, taking it to the ultra rich and big corporations,

then we can do the same today.” – Brandon Johnson

Maya: On the left, responses to those demanding that politicians stop capitulating to Israel clarified for me just how deep-seated American individualism really is and how much work it will take to overcome it. There are many people who hold progressive politics but still fundamentally believe we have to worry about “us” first, or that we can’t care about Palestine, Sudan, or Congo if people here are struggling to afford food. I’ve also been struck by conversations about how it’s a “privilege” to boycott (Starbucks and Target, of all things).

To me, all of this reveals just how entrenched and corrosive American individualism is. On a basic human level, many people do not feel a responsibility for the consequences of U.S. actions abroad, nor do they believe that what happens elsewhere has implications for life at home. That realization has been deeply instructive.

If anything, this year has made it clearer than ever that internationalism as a grounding political principle is essential to growing a coherent political movement.

What’s something that has reminded you that abolition is possible?

Alan: Here I’ll return to my first response. For me, the clarity that fascism is the long-standing project of the United States doesn’t lead to despair. It reinforces why abolitionist study, organizing, and collective imagination matter so deeply right now. If fascism is not new, then neither is resistance.

And if this moment is stripping away illusions about what the state is and has always been, it may also be opening space for more honest, collective, and transformative ways of being together—and fighting for a world beyond the one we’ve inherited.

connease: Maybe it’s the poet in me, but I see the possibilities of abolition in the natural world.

I see the answers in the trees, the way they bend and adapt, the determination to grow in the most unlikely spaces, spreading roots sideways at the edges of sidewalks, using the space available. On days clouded by overwhelm and amid so much suffering, I see an unending hope in the examples of adaptation found in plants and even in what has been labeled as weeds.

Nature is always calling and speaking to us, demanding our attention, whether through another climate catastrophe or through the seasons, though changed, continuing through the cycles of birth, growth, and death. The only question is how we will continue. What choices will we make?

In the very beginning of 2025, fires raged in Southern California, ominously echoing the prescience of Octavia Butler’s work. We read Parable of the Sower with a keener awareness of the solutions she offered in that instructive text. We were reminded of the importance of community and the enduring nature of human resilience. Parable of the Sower showed us that, even in the face of a world being dismantled from what we knew, change is inevitable. The only question is how we change. What will we abandon and what will we build?

Abolition is possible if we build a world where it can exist. Our charge is to take the opportunity to change in the direction that supports life and the natural world.

against all hope

you are here again

turning slowly

nature as chameleon

all life change

and changing again

awakening hearts

steady moving from

unnamed loss

into fierce deep grief

that can bear all burdens

-bell hooks from Appalachian Elegy (quoted in Black Liturgies)

Maya: There have been many moments this year that have reminded me that abolition is indeed possible and the current state of the world is not inevitable. I’ve been grateful to witness glimpses of abolition throughout the year: pooling funds together for loved ones, talking with students about where they see moments of possibilities, and to seeing the national conversation continue to shift on family policing. These actions, conversations, and shifts remind me that people are communal and eager to support one another.

One moment in particular that I’m also thinking about is the recent government shut down, which was the longest shutdown in U.S. history, lasting 43 days. During this time, many people lost access to government benefits—notably access to food assistance (SNAP). People came together, some creating small food pantries in their yards with “take what you need” policies. Others deepened their support of mutual aid. Households handed out canned goods and other food items in addition to candy and treats on Halloween, recognizing that many of their community members might also be hungry.

I come back to each of these moments when I think about our capacity to suspend individualism and think of one another as human beings that we are deeply connected to. These moments remind me that we know and will meet each other’s needs without being asked to.

I do not think that we can mutual aid or crowd fund ourselves out of hunger, homelessness, and the like. But I do believe that these actions and moments help us strengthen our collective muscle to care for one another. And strengthening that collective muscle makes another world more possible.

What’s one conversation we’ve had this year that you keep returning to?

Alan: The conversation I keep returning to is our discussion of Tip of the Spear with Orisanmi Burton. That conversation has stayed with me because it pushed us to think seriously—and historically—about what resistance actually looks like, rather than what we’re taught it should look like.

As you can probably tell from my earlier reflections, I’ve spent a lot of this year thinking about resistance—who gets to define it, which forms are celebrated, and which are condemned.

One of the thoughts that I keep returning to is the recognition that state institutions—prisons, police, family separation, forced institutionalization—are not neutral or passive. They are forms of normalized violence. When that reality is taken seriously, the question shifts. It is no longer simply whether violence should be rejected in the abstract, but whose violence is rendered invisible and legitimate, and whose resistance is criminalized and punished.

What Tip of the Spear helped clarify is that resisting state violence may require disruption—actions the state will inevitably label as “violent.”

That conversation reminded me that abolitionist study is not just about learning history; it’s about unlearning the moral frameworks that make state violence appear natural and justified, and about taking seriously the difficult questions that resistance forces us to confront.

connease: For the better part of 2025, I’ve been talking about and recommending Tip of the Spear by Orisanmi Burton to anyone willing to listen. By the time Dr. Ori graciously joined our meeting in August, it served as the exclamation point to many revelatory experiences. First was the recognition that we are, and have been, in an active state of war. The reframing of what I thought of and understood to be oppression was soundly turned on its head. Oppression does not begin to capture the urgency invoked by war. Beginning in the intro, Burton makes the case that we are engaged in warfare and that the experience of being Black in the Americas is to exist as a prisoner of war.

“(Queen Mother) Moore explained that Green Haven’s imprisoned men were enduring “re-captivity.” Offering an analysis made popular by her political mentee Malcolm X, she argued that prison walls made visible a condition of incarceration that is constitutive of Black life in America. Black people are a “captive nation”; the physically imprisoned had therefore been captured “doubly so.”

– Orisanmi Burton, Tip of the Spear

Recasting liberatory struggle as a response to a continuous war waged against us expands the conversations and possibilities for how we conceptualize it and engage with it. Warfare as a framework conveys a sense of greater urgency while challenging the false dichotomy between violent and nonviolent resistance, particularly as projected through the lens of Empire.

Historically, nonviolent protest has been encouraged through social norms and swift retribution from the carceral state for other forms of resistance. Yet dismantling the logic of nonviolence as a strategy through the lens of warfare reveals both its limits and the advantages it confers on the state. The cultural insistence on nonviolent resistance hypocritically obscures the depths of systemic, acceptable violence by the state. Tip of the Spear opens a necessary conversation and recasting of how we conceptualize and understand violence in the context of both domination and struggle.

“Moore then explained that it was not the captives, but the White Man who was “the real criminal.” She reminded her audience-comprised of people variously convicted of robbery, assault, rape, murder, and drug-related crimes-that none of them had ever stolen entire countries, cultures, or peoples, or sold human beings into slavery for profit. Although some of them had tried to imitate the White Man, she continued, they had never really stolen and neither had they ever really murdered. “Have you taken mothers and strung them up by their heels?” she asked. “And took your knives and slit their bellies so that their unborn babies can fall to the ground? And then took your heel and crushed those babies into the ground?.. Have you dropped bombs on people and killed whole countries of people, have you done that brothers?” Given that American Empire is constituted through apocalyptic violence and incalculable theft, Moore argued that “crimes” committed by the human spoils of war were necessarily derivative of the organized crime of the state.”

– Orisanmi Burton, Tip of the Spear

Without a doubt, Tip of the Spear and all of the thoughts and conversations it spawned in 2025 forever changed how I think of resistance, struggle, and our distinct role as prisoners of war.

Maya: We’ve had incredible conversations this year, but I can’t stop thinking about our conversation with Orisanmi Burton, discussing his incredible work Tip of the Spear: Black Radicalism, Prison Repression, and the Long Attica Revolt. I voraciously took notes throughout the entire conversation and I have not stopped returning to these notes yet. What sticks with me the most is the way his scholarship clarifies the situation we are in and what that means for us: we are at war and we must push ourselves to take seriously what that means. This helps me (us) understand how and why our efforts to advance change through laws and policy often fail. And why the terms of our conditions are always changing. This is something I continue to think about deeply and will continue to use as a grounding principle moving forward in 2026.

What are some ways you’ve kept yourself whole this year? What do you want to do better next year?

Alan: I’ll be honest: I’m not very good at this. Keeping myself whole is an ongoing struggle, and this year was no exception. Much of my energy in 2025 went into writing a new book—a memoir about my years as a family policing agent—and while that process was intense, it also felt clarifying in a way that surprised me. I’m excited for it to come out in 2027, not because it feels like an accomplishment in the conventional sense, but because I hope it becomes useful to the movement.

That writing didn’t feel like “work” in the way we usually mean it. It felt more like an act of reckoning and offering—an attempt to tell the truth about harm, accountability, and transformation in a way that might help others make sense of their own relationships to systems of punishment. In that sense, writing became one of the few ways I stayed grounded this year, even as it demanded a lot from me.

At the same time, I know that staying whole can’t only happen inside movement spaces or through political work, no matter how meaningful that work is. Looking ahead to 2026, I want to be more intentional about practices that center my body and my health—things like meditation and yoga—not as self-improvement, but as ways of cultivating presence and care outside the constant urgency of struggle. My hope is that tending to myself more deliberately will make it possible to stay in this work with greater steadiness and capacity for the long haul.

connease: Without a doubt, nature proved to be a source of refuge this year. I am proud that I leaned into urges to go outside and gaze at the trees, or consider the flowers, or sit in my car for 30 minutes watching a squirrel find a place to bury her treasure.

Many times, I fought back the capitalist tendency to rush or to tell myself I didn’t have time to indulge what my spirit and even my body felt drawn to. I listened.

Midyear, I began to focus on my health. I was intentional about deciding to take my walks outside device free, though I felt pressure to count steps and track my progress. Instead, I protected the opportunity to listen to the sounds of wind and birds, and freed my other senses to smell new grass and wild onions, and witness the sights of a burgeoning spring, a summer in full bloom, and a fall marked with the deepening palette of change.

My inclination to seek the solace and wisdom of nature is a spiritual urge to reconnect to that which racial capitalism steals through time, or the mistaken assumption that reveling in nature is frivolous or inconsequential. Yet before White supremacy and settler colonialism established their foothold in the world and our consciousness, we moved with the flow of the seasons and the earth. Thus, any move toward that which we’ve lost is a critical act of resistance.

I believe in living.

I believe in the spectrum

of Beta days and Gamma people.

I believe in sunshine.

In windmills and waterfalls,

tricycles and rocking chairs.

And i believe that seeds grow into sprouts.

And sprouts grow into trees.

I believe in the magic of hands.

And in the wisdom of the eyes.

I believe in rain and tears.

And in the blood of infinity.

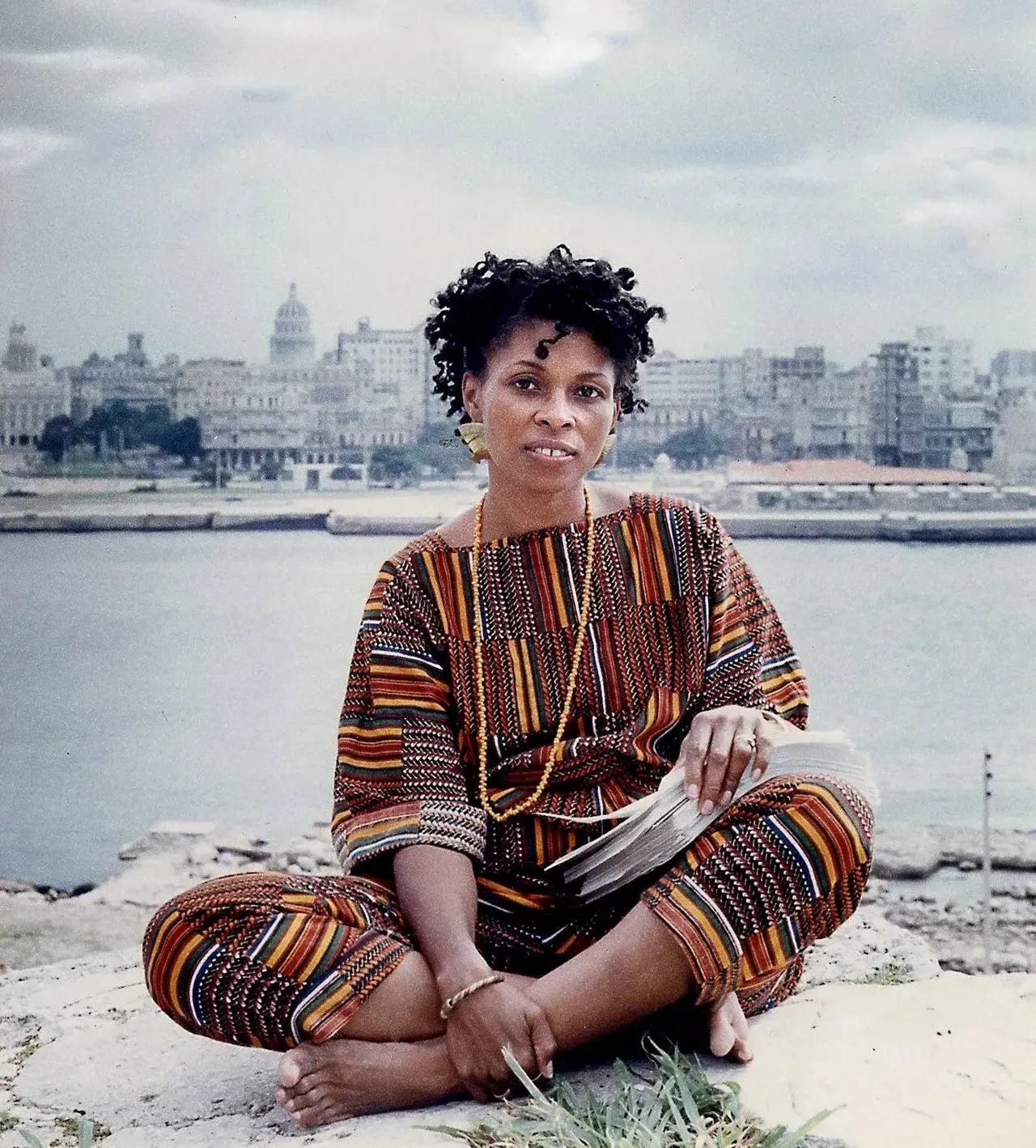

– from Affirmation by Assatta Shaku

Maya: Something I did well this year was being more disciplined about journaling and sitting in discomfort. I think it’s easy for me to just keep going and moving through hard feelings instead of really sitting with them, and this year I pushed myself to slow down quite a bit. Relatedly, I spent the last few days of the year in the mountains and stayed off of my phone for the most part. Those days were a reminder that I need to do this more regularly. Moving my body, pushing myself on tough hikes, dealing with sweat and rain, and being completely aware of each step—making sure my foot isn’t on a loose rock, staying alert for bears or other creatures—is a practice in being fully present in my body and of working with, rather than against, nature. Each step, each breath, each push, and each moment of ease is fully felt.

Even if I can’t get away from the city frequently, I can work to create more moments of stillness in my life, appreciate both human and non-human forms of life, and be more aware of the time I’m spending on my phone. I recently read that social media makes time move faster because phone use dulls our awareness of our surroundings and weakens our memory of the present. Simply put, scrolling impairs our “awareness of the present and your memory of the past.”

Time moves more slowly in a way that makes me feel less anxious when I’m not scrolling my time away. It gives me space to sit with my feelings, thoughts, and discomfort instead of scrolling past them.

I don’t do this enough and I’d like to do more of this in 2026.

What’s one hope for 2026? Something you’d like to see more of from movements on the left?

Alan: One hope I carry into 2026 is not a renewed faith in electoral politics, but a clearer set of political expectations. I no longer believe elections, on their own, will bring about the kind of change we need. At the same time, the election of Zohran Mamdani as mayor of New York felt instructive—not because it restored my belief in the system, but because it signaled a shift in what is considered politically possible.

What stood out most was Mamdani’s unapologetic support for Palestinian liberation, and the fact that this position was not treated as disqualifying by voters. For so long, solidarity with Palestine has been framed as an electoral liability, something to be softened, hidden, or abandoned in the pursuit of “viability”—something we saw play out very clearly in last year’s Presidential election. Seeing that narrative fail—seeing a candidate win without retreating from a clear anti-colonial stance—felt like an important crack in the logic that has disciplined the so-called left for decades.

My hope for 2026 is that this becomes a baseline rather than an exception. I want to see support for Palestinian liberation—and a commitment to ending U.S. support for Israeli violence—become a litmus test for anyone claiming the mantle of the left. Not a symbolic statement, not a vague call for peace, but a clear refusal to participate in genocide, apartheid, and settler colonialism.

That shift wouldn’t mean elections suddenly save us. But it would reflect something deeper and more important: movements forcing clarity, refusing moral compromise, and making it impossible to build political legitimacy while standing on the side of empire. For me, that’s where hope lives—not in the ballot itself, but in the pressure movements apply to redefine what is acceptable, sayable, and possible.

connease: My one hope for 2026 is the same hope I had for 2025, that we will galvanize a mass movement to slow the gears of racial capitalism. I hope that there is more widespread education and acknowledgement that our capital and labor are assets we can effectively leverage. Though the level of coordination and sacrifice can feel overwhelming at times, I am hopeful that examples like the sustained boycott of Target give people more faith in collective action.

That is my audacious hope, even as the 1% increasingly tightens its grip on resources and hastens the extractive mechanisms that drive suffering. I hope, while also observing the calculated efforts to distract us through media campaigns that utilize AI and bots to foment outrage and pit groups against each other.

I hope we realize, sooner rather than later, that the solutions lie in uniting against our common enemy in solidarity and striking back by withholding our dollars and labor against the greed and inequality that threaten us all.

Maya: I think we have a tough road ahead in this country. It’s only been a year of the current administration, and it already feels like three. At the same time, I’m witnessing a broader rise in conservatism. People are re-embracing “traditional” values; young people are returning to religion in ways that feel tied to conservative politics; slurs are resurfacing; and homophobia feels increasingly normalized. Right-wing content is ubiquitous across social media platforms, and it often feels like any hobby or interest can become an expressway to an alt-right pipeline.

I am deeply concerned about the political and social direction we are heading in. And alongside that concern is a growing realization that we lack the political analysis and collective consciousness needed to meaningfully push forward. Many people are still asking, “What if Kamala had been president?” I worry that this question reflects a desire to return to what felt familiar or comforting for some, rather than to move toward real structural change.

To that end, I want to see real strides in our collective political analysis. I want mass protest grounded in rigorous analysis and strategic action. I want our ability to evaluate elections and candidates to move beyond where it is now. And more than anything, I want political education to be centered, not as an afterthought, but as a core practice of building power.

Below, we’ve compiled a list of causes, organizations, and funds we’ll be supporting in 2026 and beyond. We hope you’ll support what you can too.

Welcome Home Fund for Marie Mechie Scott

Support Sheena King’s commutation efforts with the purchase of her book Submerged: On Healing from Abuse While Navigating a Lifetime of Imprisonment

I have read your pieces throughout the year. Thank you for writing this thoughtful end of the year piece that resonated with me. May we continue in truth and community in the new year.

Phenomenal piece. The observation about the UnitedHealthcare response crystallizing a shift in how people understand legitimacy is really penetrating. What struck me most was the framing around slow bureaucratic violence versus visible acts of resistence, because it flips the usual moral calculus most people operate under. I've been grappling with that same tension in conversations where folks who are sympathetic to abolition still recoil when the discussion turns to what resistance might actualy require. The warfare framework from Burton def makes that conversation more urgent and honest.