Rehearsing Freedom

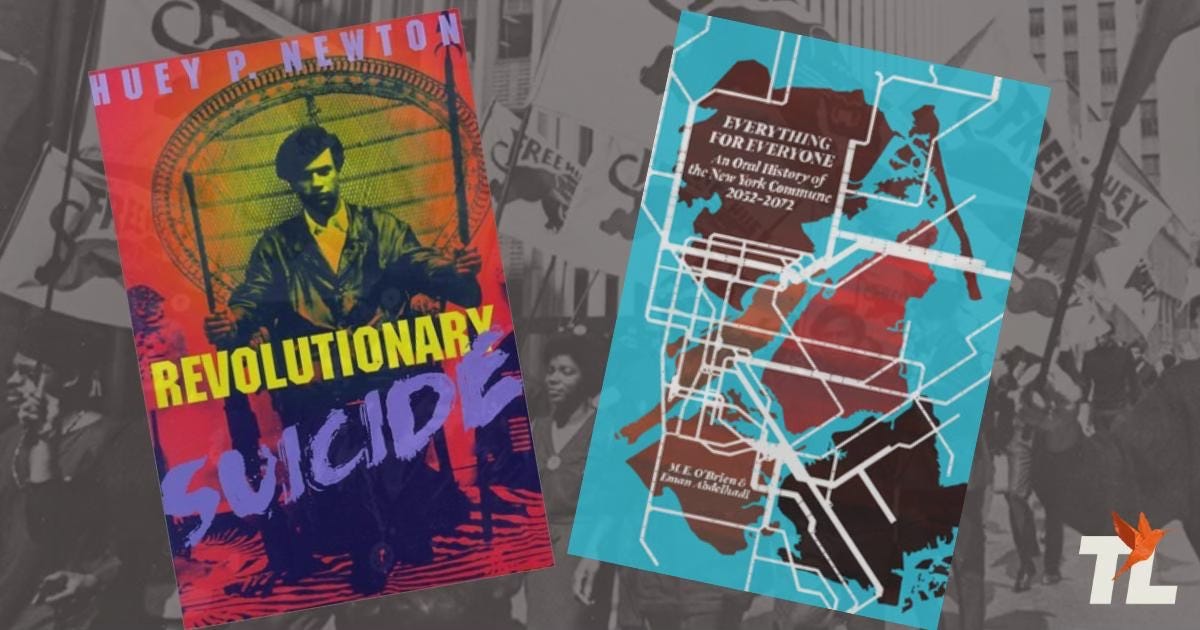

Reading Huey P. Newton alongside Everything for Everyone

I’m not a voracious reader. I’ve never been the kind of person who moves through a stack of books every month or always has three books going at once. Like a lot of people, it can be hard to carve out the time and focus that deep reading requires. Life crowds it out. Work crowds it out. And reading has never felt like leisure to me.

But this year, I’ve been trying to be more intentional about my political education—not just skimming articles or reacting to the news cycle, but slowing down and sitting with the kinds of books that shape how we understand the world and what’s possible beyond it. So this month, as we’ve been reading Everything for Everyone, I decided to return to a book I had read before but didn’t think I had fully absorbed: Revolutionary Suicide by Huey P. Newton.

Reading them together, I’ve been struck by the connections that exist across time. One looks back at revolutionary struggle in the 1960s. The other looks forward to a world after capitalism has fallen. Reading them side by side feels less like comparison and more like a conversation. One asks what it will take to get free. The other asks what freedom might actually feel like.

In Revolutionary Suicide, Newton refused both despair and fantasy. He wrote about what he called reactionary suicide—the slow death that comes from accepting humiliation, powerlessness, and the inevitability of suffering under oppressive systems. And then he offered another choice:

“It is better to oppose the forces that would drive me to self-murder than to endure them. Although I risk the likelihood of death, there is at least the possibility, if not the probability, of changing intolerable conditions.”

For Newton, revolution wasn’t spectacle. It was a commitment to live with dignity—even when the cost was high. He clarified:

“We have such a strong desire to live with hope and human dignity that existence without them is impossible.”

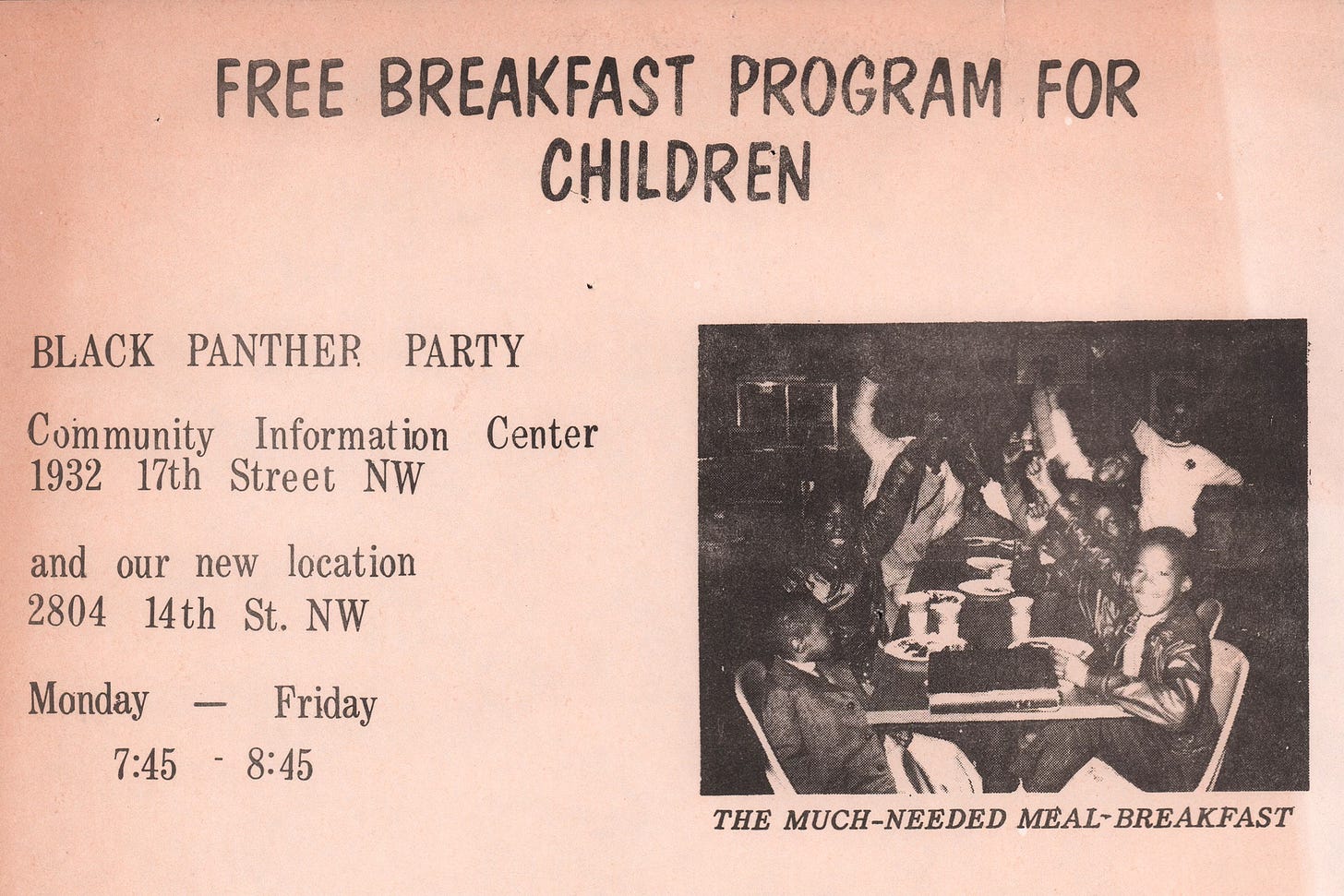

That framing is important because it reframes revolution not as destruction, but as insistence—insistence for a better world. And for the Black Panther Party, that insistence took material form. They didn’t separate theory from practice—their politics showed up as survival programs: free breakfasts, clinics, legal aid, transportation, childcare. Survival itself was the ground on which revolution became possible.

Everything for Everyone picks up on the other side of that struggle. Instead of asking what we must endure or risk, it asks, What happens after we win?

The book is structured as an oral history, told through many voices rather than a single protagonist. We hear neighbors remembering how they seized food depots, opened hospitals, transformed housing, and built new forms of collective life. Food is shared. Care is organized together. People begin to heal through participation rather than punishment. It doesn’t read like utopia. It reads like practicality. What happens when profit and policing are no longer the organizing principles of society?

What remains isn’t chaos. It’s care. It’s shared responsibility. It’s the slow, everyday work of keeping each other alive. In that sense, the world it imagines feels less like speculative fiction and more like the Panthers’ survival programs in full operation, extended across an entire society.

Reading these two books together, especially during Black History Month, makes clear how much today’s abolitionist imagination grows out of the Black radical tradition. Newton asks, What must we risk to end this system? The commune answers, Here is what becomes possible when we do. Newton describes the courage required. The novel shows us the world that courage might create. Newton grounds revolution in the material work of survival. The commune begins in that same place—food, housing, and care. Both center ordinary people acting together. In both, revolution is not heroic. It is communal.

Black History Month is often framed as remembrance—a looking back. But the Black radical tradition has always been forward-facing. Newton’s writing wasn’t meant to be a memorial. It was meant to prepare people for struggle. Speculative fiction like Everything for Everyone does something similar. It stretches our political imagination and helps us picture worlds we’ve been told are impossible. Both forms—autobiography and fiction—help us rehearse freedom before it arrives. That’s part of why Toward Liberation exists. Not just to understand what has been, but to practice imagining what could be.

If there’s a shared lesson running through both books, it is that revolution doesn’t begin with collapse. It begins with care—with people meeting each other’s needs, sharing resources, and building structures that make the old systems unnecessary.

The question isn’t whether a different world is imaginable. These books make clear that it is. The harder question is, What are we building right now that prefigures that world? Where are our survival programs? Where are we practicing collective care? How are we making punishment and profit obsolete in our own communities?

Because the future imagined in Everything for Everyone doesn’t appear out of nowhere.

It grows out of us. Out of the everyday work we choose to do together. Out of the ways we care for one another now. Out of the political education that helps us see beyond what this system insists is inevitable.

This is another reason Toward Liberation exists. Not just to analyze the world as it is, but to read, study, and imagine together—to learn from the long lineage of abolitionist thinkers, organizers, and dreamers who have always insisted that something else is possible.

We read writers like Huey P. Newton not as history, but as instruction. We read books like Everything for Everyone not as fantasy, but as rehearsal. Because imagining freedom together is part of building it.

Alan

Join us on February 24th at 6:00 PM Eastern to discuss Everything for Everyone: An Oral History of the New York Commune, 2052-2072, with special guest, co-author M. E. O’Brien.