The Abolitionist Papers that Influenced Our September Read

When I began writing my book, one of the first things I started to research was how enslavers created narratives about enslaved mothers that they didn’t have the same feelings toward their children as white mothers did. As such, they weren’t really harmed when their children were sold away. Tracing these narratives was important because I wanted to demonstrate that the narratives we have today about Black mothers - stories about “welfare queens” who only have children to make more money - actually began centuries ago and persist today as a means of justifying how the state continues to forcibly separate their children from them.

Many of these ideas originated in the writings of Thomas Jefferson, who wrote frequently on the inferiority of Black people as a means of justifying their enslavement. On their experiences of grief and pain, he wrote, “Their griefs are transient. Those numberless afflictions, which render it doubtful whether heaven has given life to us in mercy or in wrath, are less felt, and sooner forgotten with them. In general, their existence appears to participate more of sensation than reflection.”

These ideas were echoed decades later by enslavers, including Thomas Chaplin, who wrote in his journal after selling away ten enslaved children, “The Negroes at home are quite disconsolate, but this will soon blow over. They may see their children again in time.”

Once I had these narratives documented, I began researching how abolitionists of the time tried to counter these narratives and discovered the trove of abolitionist newspapers, flyers, and other written materials that were disseminated in underground networks primarily to the Northern states as a means of generating support for the burgeoning abolitionist movement. These writings dep tale after tale documenting the horrors of family separations and how deeply these impacted those whose children were taken and sold away from them. One of the stories I found most moving and included in my book was a personal account in the American Anti-Slavery Almanac of 1841 titled, “Can Slaves Feel?” -

This account vividly demonstrates the horror and pain that an enslaved mother felt after her child was taken from her. It was stories like these that began to reach those who either ignored or were ambivalent about the horrors of slavery.

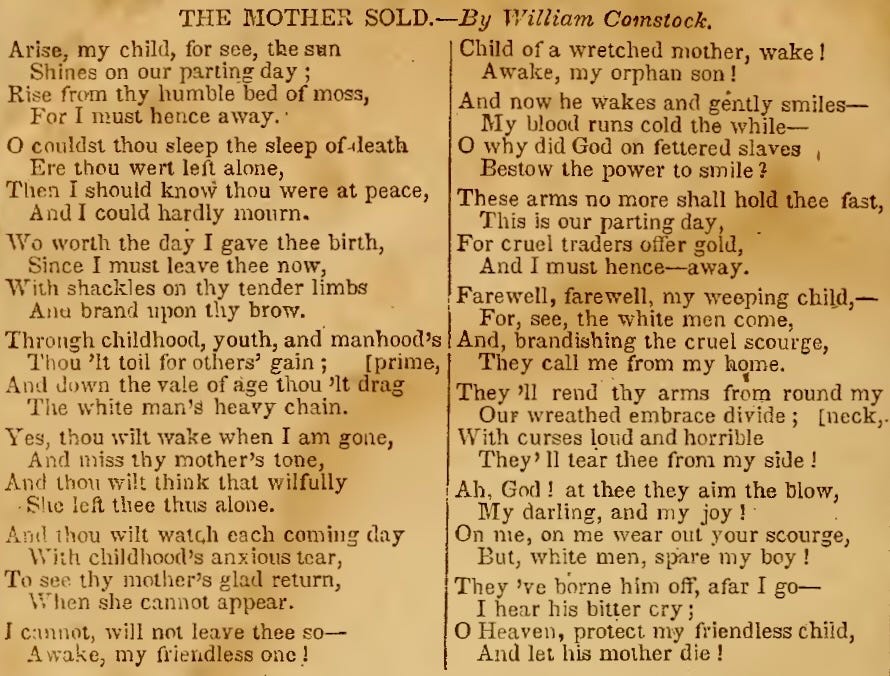

These papers also contained beautiful works of poetry that tell similar stories. This poem from the Anti-Slavery Almanac of 1838 tells a story of separation from a mother’s perspective:

Stories and poems such as this are difficult to read, but they were necessary to counter the narratives that enslavers wanted the public to believe. These stories and poems also demonstrate the power of the written word in shaping the ideas that undergirded the abolitionist movement and in moving a previously ambivalent public to act.

I wrote Confronting the Racist Legacy of the American Child Welfare System in hopes that it would become part of this legacy of abolitionist writings that propel a movement forward. Today, we are challenged by the same ambivalence toward family separations that once existed during the era of chattel slavery. Yet, what if we can begin to shift this ambivalence? What if we could recreate the shared understanding of the horrors of family separation that writings such as those included here were able to do centuries ago? I hope this book can become just a small part of the work so many are doing today to shift this ambivalence and move our movement forward.

I look forward to sharing more of the early abolitionist writings that influenced my book. And save the date for our next virtual discussion on Thursday, September 28 at 6:00 PM Eastern - more details to come. I’m really looking forward to seeing you and hearing your thoughts!