We Are the Change We Wish to See

AKA To the Person Who Called Me a Fuckwad...

We can examine the ways we engage with ourselves and each other. We can ask ourselves if our behavior is rooted in punishment, exile, and abandonment or if it offers invitations and creates possibilities to transform individual and collective conditions. We can reach toward the world we long for by using every day as a practice ground in which we generate new possibilities that can proliferate and ultimately reshape our world. - Practicing New Worlds: Abolition and Emergent Strategies, Andrea J. Ritchie

I often return to this quote from Andrea Ritchie for several reasons. First, it was through this quote that I discovered Emergent Strategy, which sparked a learning journey that reshaped my understanding of my role in the abolition movement and how I can contribute to it daily. More recently, I’ve found myself revisiting it in light of ongoing frustrations in this post-election climate, where applying these ideas in my everyday life has felt particularly challenging.

I've written about this before, and I keep telling myself I’ll stop writing about my frustrations with Democrats and the Democratic Party—but here I am. That said, I believe this will be the last time. I’m hoping my act of writing this will solidify some things for me that I can put into practice more effectively.

As many of you know, leading up to the election, there was significant disagreement among those who I’ve previously referred to as “Democrats” and “the Left”—though I recognize that this framing itself is part of the problem, and I’ve contributed to it. A better way to describe this might be to say disagreement among people who voted for Joe Biden in 2020 or, more simply, those who did not want Donald Trump to be president—both categories I belong to. The primary point of contention was Joe Biden’s, and later Kamala Harris’s, support for genocide in Palestine, which led many people, myself included, to either abstain from voting or to support a third-party candidate.

After the election, there was a brief moment when many of those who opposed Donald Trump’s presidency seemed to recognize the need to work together—both to resist his agenda and to prevent someone with a similar agenda from leading the country in the future. There were encouraging signs of a radicalization among Democrats, from widespread outrage at supposedly progressive news hosts who eagerly met with Trump to collective anger over his wave of executive orders. But this moment of radicalization quickly faded and was firmly crushed after Trump announced his plans to “take over” Gaza and turn it into some kind of beachfront resort—an effort that would require a complete ethnic cleansing of the area (which many, including myself, would argue was simply a continuation of the previous administration’s agenda, but this is what reignited much of the earlier divisions).

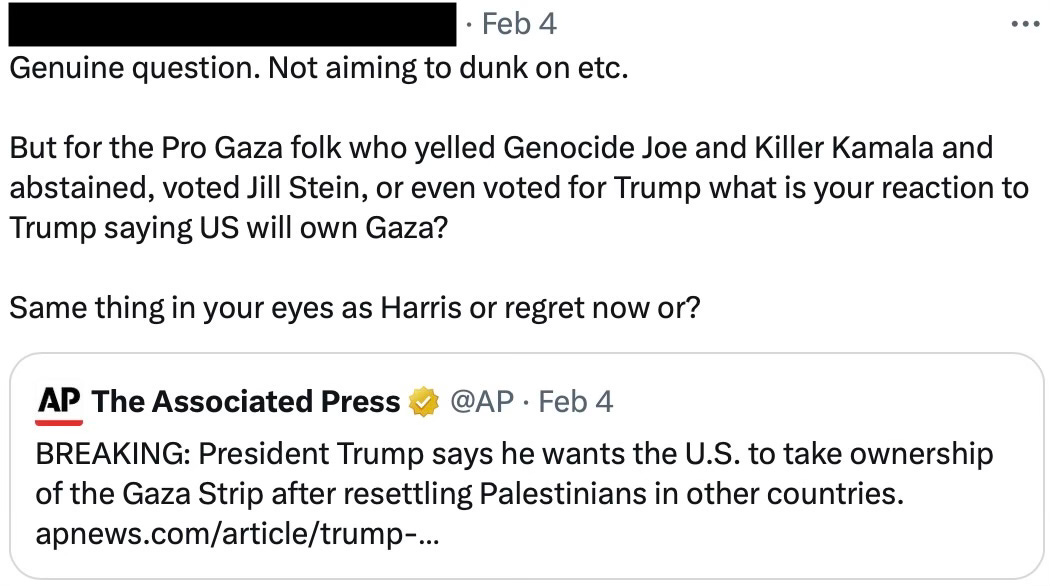

This is one of the first posts I saw shortly after Donald Trump announced his plans for Gaza during a press conference with Benjamin Netanyahu:

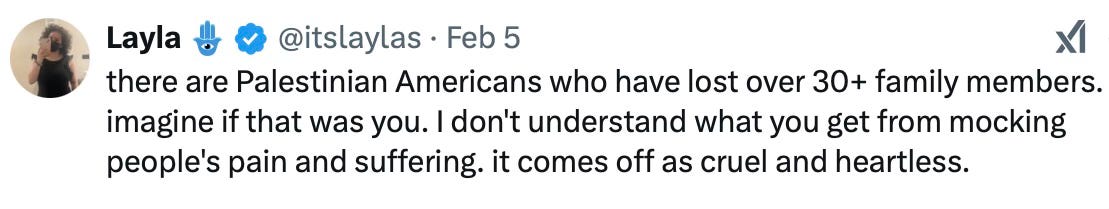

This was intended as a passive-aggressive insult toward those of us who chose not to vote for Kamala Harris—implying that we didn’t understand what was at stake in this election, or that we should have simply ignored Kamala Harris’s commitment to genocide and instead voted for Symone Sanders’ imperialist candidate of choice because she was somehow a “lesser evil.” However, when challenged by some of the people she aimed to insult, including very poignant replies like this:

Symone Sanders simply replied:

So now, not only are we being dismissed as too ignorant to understand that elections have consequences, but when we push back on this narrative, we’re reduced to nothing more than “hit dogs.” The reality is that those of us who chose not to vote for Harris were fully aware of the consequences of elections. We knew that a Trump presidency would be devastating for Palestinians—but we also knew that a Harris presidency would bring the same harm by continuing the policies of the Biden administration, which is precisely why we chose to vote differently.

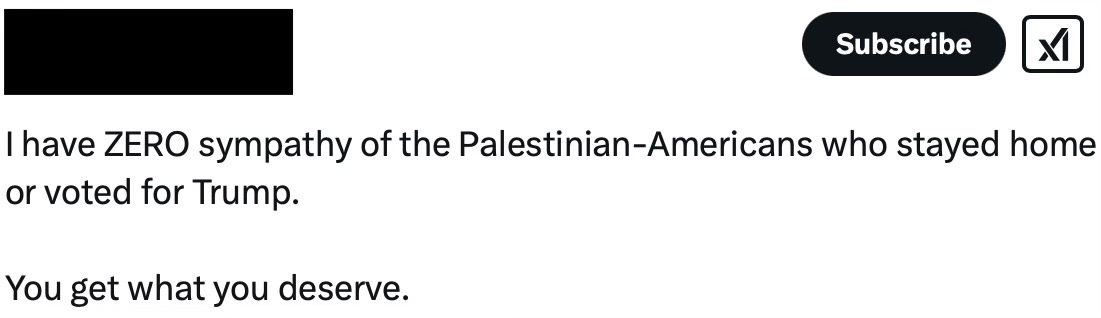

But Symone Sanders was not alone in her efforts to shame us. Similar posts from others followed:

So rather than those in power reflecting on their choices—rather than Democrats acknowledging, “Maybe if we hadn’t been so committed to genocide, things could have turned out differently”—the blame is placed on us. Those of us who chose not to vote or supported a third-party candidate are framed as the problem.

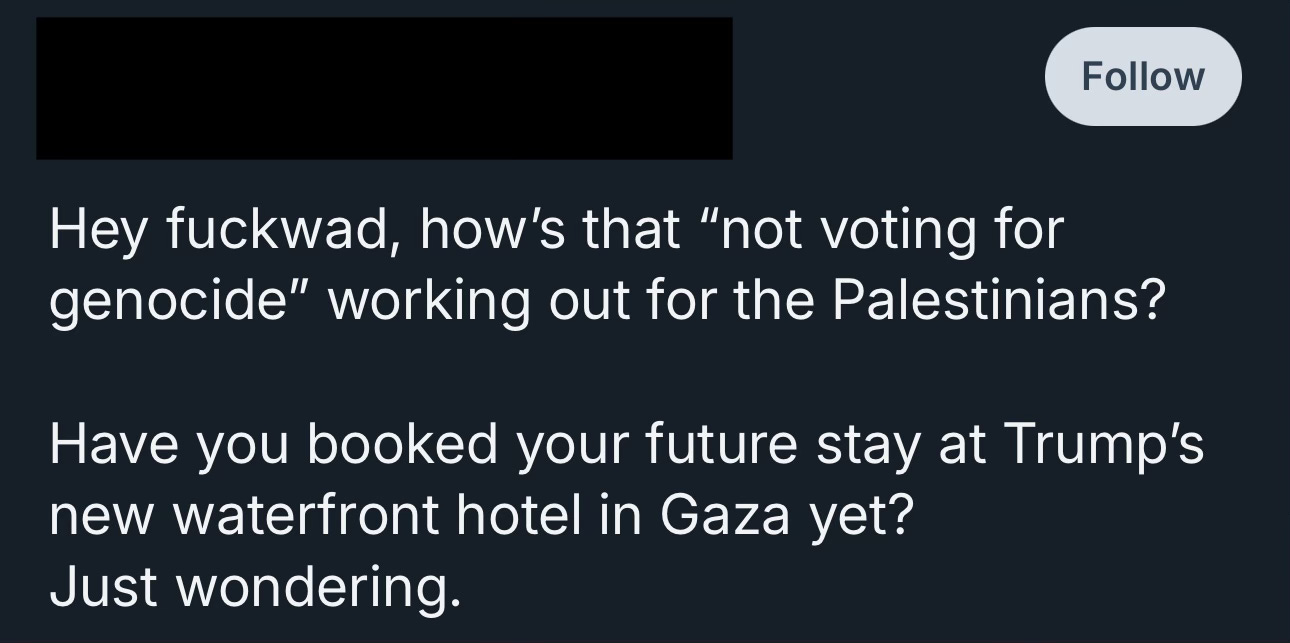

What has been most disturbing about the rhetoric in the past few weeks is the way some have openly disparaged Palestinian-Americans—not just through insults, but by suggesting they deserve the cruelty being inflicted upon them, as seen in comments like this:

In another horrifying example of this, following Donald Trump’s announcement of his “plans” for Gaza, Layla Elabed, co-chair of the Uncommitted Movement, released this statement:

In response, this is what a former aide to Kamala Harris had to say:

“Clowns.” That’s how at least one person who worked on the Harris campaign views those who tried—unsuccessfully—to get their candidate to commit to a ceasefire as a way to win over thousands of potential voters who had been demanding it. What struck me about this was remembering one of the pivotal moments in the Uncommitted Movement’s efforts—their formal request to the Harris campaign for a Palestinian-American speaker at the Democratic National Convention this past August.

The request was simple: a two-minute slot for a Palestinian-American to deliver vetted, pre-approved remarks in which they would endorse Kamala Harris for president. This request was denied. Despite the clear opportunity to repair months of damage and potentially secure tens of thousands of previously “uncommitted” voters, the campaign refused because granting it might have upset one of the billionaires backing their campaign. And as many of us have come to understand, in electoral politics, the interests of these billionaires are the only ones that truly matter.

This is starting to feel a bit like an extended rant now. In part, this is because this is what the comments I receive on social media look like these days:

But this brings me back to my original intention in writing this. I’m frustrated. This is not how we fight fascism. This is not what solidarity looks like, and this is not the way we work together to build a better future.

I want to be very clear—I recognize that I’ve also been guilty of saying things that certainly came across as shaming over the past few weeks as well as in the months leading up to the election. I haven’t publicly called anyone a “fuckwad,” but the thought has crossed my mind. And every time it does, I remind myself of what I want to learn from Andrea Ritchie, adrienne maree brown, and Emergent Strategy—I think about what it means to “examine the ways we engage with ourselves and each other” and ask myself if my “behavior is rooted in punishment, exile, and abandonment, or if it offers invitations and creates possibilities to transform individual and collective conditions.”

This has been my struggle over the past few months as I know my practice of Emergent Strategy is not where I want it to be.

As I wrote about earlier this month, in addition to reminding myself of the words of Andrea Ritchie, I’ve often come back to this quote from George Jackson, which connease also referenced in her post earlier this week:

Settle your quarrels, come together, understand the reality of our situation, understand that fascism is already here, that people are already dying who could be saved, that generations more will die or live poor butchered half-lives if you fail to act. - Blood In My Eye

Although this was written over 50 years ago, this remains the only viable path forward. We cannot be fighting each other. To be clear, this doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be fighting Donald Trump, Elon Musk, and everyone else pushing their fascist agenda. But it also means we should be fighting everyone in the Democratic Party who has been advancing a fascist agenda for decades—just with a slightly different public relations strategy. Those of us who are not part of the elite billionaire class need to be united in our efforts to fight against this ruling class and the politicians from both major parties who serve their interests.

For myself, this involves remembering this other quote from Andrea Ritchie’s Practicing New Worlds:

Emergent strategies teach us that change happens at the smallest levels, that bringing attention to how we talk to ourselves and interact with each other means we can start practicing abolition here, now, and freshly each day, at a scale that is accessible to every one of us.

So to the person who called me a fuckwad, I totally get where you’re coming from—I really do. We both wanted something very different than what we have right now, and we both made decisions in the recent election based on this desire. But calling each other fuckwads is not going to get us where we want to be.

Over the next few months, as we continue studying Emergent Strategy, I’m hoping to more deeply internalize how to practice this in my daily interactions. I’m also excited to share that our March selection will be Andrea Ritchie’s Practicing New Worlds: Abolition and Emergent Strategies, which as I’ve shared here, was my introduction to these ideas.

The principles of Emergent Strategy are not simple or easy, and neither is building solidarity, particularly when very real divisions have challenged our ability to work together. But working together has to be our path forward, and I’m looking forward to continuing to build this space and growing and learning together. We are the change we wish to see, and we have the power to bring about this change.

In solidarity,

Alan

PS: I hope you’ll join us this Wednesday (02/26/2025) on zoom to discuss our February read, Parable of the Sower! (as always, reading the book is not a requirement)

I have never read "Parable of the Sower" so I took this month's club reading assignment to finally read it.

Here are some things that were of interest to me:

What exactly is the US government during the period of "Parable of the Sower"?

I got that it was mainly a plutocracy in which massive corporations "employed" (read: enslaved) (non)drugged addled people, and their descendants with corporate credits which they must spend in corporate towns. We are never really told what impact these corporations have on power in Washington DC. Bankole tells us that the federal system still exists but he did not know that his sister's home had burned down...

The police are a fee for service organization/make things worse: ""But... couldn't we call the police?" "For what? We can't afford their fees, and anyway, they're not interested until after a crime has been committed...""(80) "And they knew the cops liked to solve cases by "discovering" evidence against whomever they decided must be guilty. Best to give them nothing. They never helped when people called for help. They came later, and more often than not, made a bad situation worse." (122)

Earthseed: "God is neither good nor evil, neither loving nor hating. God is Power. God is Change. We must find the rest of what we need within ourselves, in one another, in our Destiny." (251) "The earthquake had done a lot of damage in Hollister, but the people had not gone animal. They seemed to be helping one another with repairs and looking after their own destitute. Imagine that." (262)

Why does Lauren Olamina see her sharing/hyperempathy as her weakness? Why does she not see her sharing as connection? Does her sharing play into her evolving understanding of Earthseed?

Alan, this was meaningful to me and lays out some great opportunities for me to learn and change. I have no idea why Substack sent it to me today, or why Substack does many of the things it does, but I’m grateful that it sent me this post that I missed in February. I have been meaning to join the study group, and I’m going to go now to find the next date and reading so I can contribute in some way. Thank you so much for sharing this piece!